Have you ever pictured yourself squinting into a blue glow under a mountain, feeling slightly foolish for wearing bright socks but oddly proud that you remembered a headlamp?

Exploring The Ice Caves Of Mount Shasta

This piece is about the ice caves that form on and around Mount Shasta, a mountain that seems to collect legends the way you collect ill-advised souvenirs. You’re going to get practical information, safety advice, route ideas, and a little lateral human commentary, because you’ll want both facts and a sympathetic narrator who understands why you packed three extra pairs of gloves.

What are the ice caves on Mount Shasta?

These ice caves are chambers of ice and rock created by combinations of glacial action, meltwater channels, steam vents, and occasionally volcanic heat. They’re not permanent rooms in a hotel; they’re ephemeral, shifting, and often fragile, which is part of their allure and their danger.

How they form

Ice caves on Mount Shasta usually form in places where snow and ice are melted by underlying heat or by runoff, carving out voids beneath or within glaciers and snowfields. Some are the result of meltwater rivers tunneling under ice, others form when fumarolic heat from the mountain melts ice into caverns, and some occupy lava tubes that become lined or filled with ice. In short: these caves are a product of geology, weather, and luck.

Why they’re special

They produce intense blue and turquoise light that photographers chase, and they’re compact laboratories of seasonal change: you can watch a cave appear, grow, and sometimes collapse within a single year. For you, the experience can feel like stepping into a refrigerated cathedral with better acoustics and worse plumbing.

This image is property of images.unsplash.com.

Where you’ll find them

The ice caves tend to appear on the glaciers and steep snowfields of Mount Shasta’s flanks, often accessible from established trailheads like Bunny Flat on the south side. The northern and northeastern glaciers (Hotlum, Wintun, Whitney, Konwakiton, Bolam, and others) create conditions suitable for caves. However, exact cave locations shift from year to year and many are on steep, avalanche-prone terrain.

Why location matters

Because these caves can collapse or become hidden beneath new snow, their safety and accessibility hinge on micro-conditions: recent melts, weather, and recent storms. That means a cave you read about in last year’s blog post might already be gone. For your safety and the health of the caves, you’ll want to rely on up-to-date reports and local ranger advice before setting out.

When is best to visit

Timing is a balancing act. Late winter and early spring often offer well-developed ice caves and high, cool snowpack that supports travel; late spring and early summer can produce dramatic melt-sculpted caverns but also higher risk of collapse. By midsummer many caves have collapsed or are too unstable to enter.

Seasonal nuances

- Late winter to early spring: stable snow bridges but deep avalanche risk after storms; great ice but very cold.

- Late spring: impressive melting and sculpted caverns; beware of unstable roofs and increased water flow.

- Summer: caves often collapse or become unsafe; ice may remain but is usually more exposed and brittle.

- Fall: refreezing can make surfaces treacherous and caves can be deceptive in their stability.

This image is property of images.unsplash.com.

Permits, regulations, and local contacts

Before you set off, check with the Mount Shasta Ranger District (Shasta-Trinity National Forest) for current trailhead closures, permit requirements, and safety notices. Regulations change with conditions, and the forest staff often have the latest scoop. If you plan to camp, climb, or travel overnight in the Mount Shasta Wilderness, permits and registration may be required.

Why you should contact rangers

Rangers can warn you about avalanche conditions, recent cave collapses, parking rules, and sensitive areas to avoid. You might prefer a ranger’s admonition to a more dramatic blog-post caution written by someone who once wore shorts on a glacier.

Getting there: access and trailheads

Most approaches begin at well-known trailheads. Bunny Flat (also called Upper Soda Springs or Bunny Flat picnic area) is the most popular southern trailhead and a common starting point for climbers and day hikers heading to central glacier areas. From trailheads you’ll typically follow established routes toward the glaciers where caves can form.

Practical travel tips

- Road access: check for seasonal closures and snow chains, because the last few miles can be rough or gated in winter.

- Parking: some trailheads have limited parking; arrive early or have a backup plan.

- Navigation: GPS is helpful but don’t depend solely on it; bring a map and compass and know how to use them, especially when whiteout or fog appears.

This image is property of images.unsplash.com.

Routes and difficulty

Different approaches offer varying levels of difficulty and exposure. Below is a simplified comparison table to help you match your experience level with a likely route. Note that routes to caves are often off-trail and variable; this table lists common access corridors rather than specific cave approaches.

| Route / Corridor | Typical start | Difficulty | Typical travel time (one-way) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bunny Flat → Avalanche Gulch corridor | Bunny Flat | Moderate to Strenuous | 2–6 hours (to glacier/cave area) | Common summit approach; avalanche-prone slopes; requires snow travel skills in season |

| Clear Creek / Panther Meadows corridor | Clear Creek parking/others | Moderate | 2–5 hours | Less steep approaches to certain glaciers; long walk if conditions force detours |

| North/East glacier approaches (Hotlum/Wintun) | Various north access points | Strenuous | 3–8 hours | More remote; often technical and icy; glaciers are present year-round |

Choosing a route

Select a route that matches your skills in snow travel, crevasse awareness, and route-finding. If you haven't practiced glacier travel—or if your crampons and you are still on a relationship-building phase—consider hiring a guide.

Gear and clothing: essentials and nice-to-haves

Going near ice caves requires you to plan for cold, wet, and unstable conditions. Below is a table with a practical checklist to help you pack without turning your pack into a moving storage unit of regrets.

| Item | Purpose | Recommended specifics |

|---|---|---|

| Helmet | Protects from falling ice and rock | Climbing helmet, properly fitted |

| Headlamp + spare batteries | Light inside dark caverns | 400–1000 lumens with red-light mode |

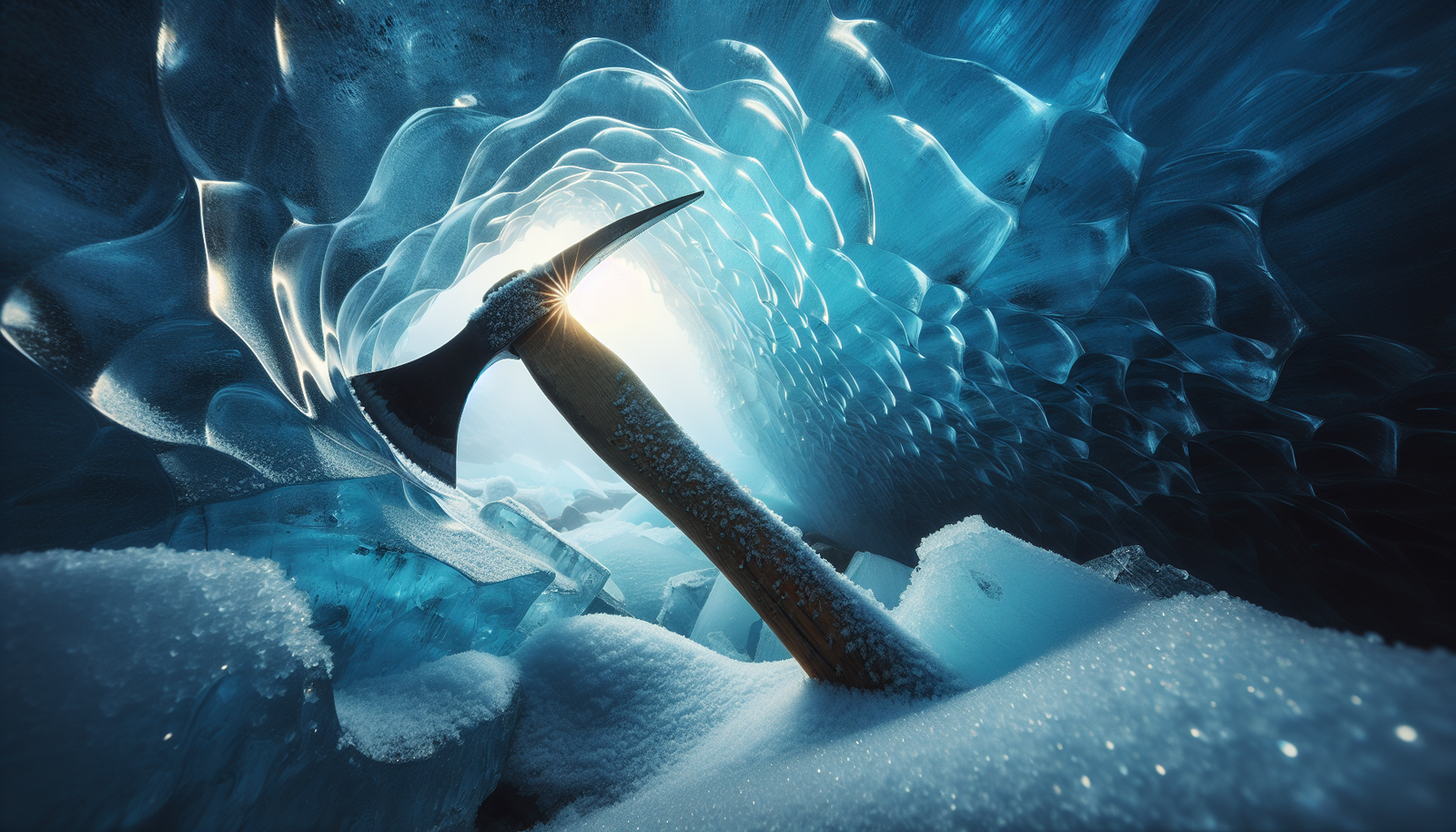

| Ice axe | Self-arrest and general stability | Classic mountaineering axe |

| Crampons | Traction on ice | 10–12-point crampons compatible with your boots |

| Mountaineering boots | Warmth and support | Stiff-soled, insulated crampon-compatible |

| Rope + harness | Crevasse protection or for steep sections | 30–60 m dynamic rope, single-pitch harness |

| Warm layers | Core insulation | Base layer, mid-layer, insulated jacket |

| Shell (waterproof/windproof) | Protects against meltwater and wind | Breathable hardshell |

| Gloves (multiple) | Keep hands functioning | Thin liner + insulated waterproof overgloves |

| Emergency bivy/blanket | Shelter if stuck overnight | Lightweight, packable |

| Map & compass | Navigation backup | Topo map of Mount Shasta area |

| Avalanche safety gear (if relevant) | For travel in avalanche terrain | Beacon, probe, shovel; know how to use them |

| Communication device | Call for help beyond cell service | Satellite messenger (Garmin inReach) or PLB |

| First aid kit | Treat injuries | Include blister care, trauma supplies |

| Food & water | Energy and hydration | High-calorie snacks; insulated bottles to prevent freezing |

| Camera protection | For shooting inside damp, cold caves | Dry bag, lens cloths, spare batteries kept warm |

Choosing technical gear

If you plan to actually enter a cave rather than just view it from the rim, treat it like a technical alpine objective. Crampons, helmet, rope, and a partner who knows how to belay and arrest are not optional. The cave may look like a postcard, but postcards don’t do first aid.

Safety hazards and how to mitigate them

Ice caves are unstable, and the list below covers common hazards. Treat them seriously and plan to mitigate each one.

| Hazard | Why it’s dangerous | How to reduce risk |

|---|---|---|

| Roof collapse | Melt and stress can make cave ceilings fragile | Do not enter unstable caves; observe from a safe distance; consult rangers |

| Falling ice / seracs | Chunks can fracture from above | Wear a helmet; avoid standing beneath overhangs |

| Avalanches | Snow on steep slopes above caves can slide | Check avalanche forecasts; travel with proper gear and training |

| Crevasses | Hidden openings in glaciers | Travel roped in glacier terrain; practice rescue skills |

| Hypothermia | Cold, wet conditions can sap strength | Use layered clothing; carry spare dry clothes |

| Rapid meltwater | Sudden surges can occur during warm spells | Avoid caves during warm afternoons or rain; watch for waterflow |

| Poor lighting & disorientation | You can get lost or injured in the dark | Carry headlamp; mark exit; limit deep penetration |

| Rockfall | Freeze-thaw loosens rock above caves | Keep distance from steep walls; wear a helmet |

A practical safety mindset

Assume the cave is more dangerous than it looks. Your brain will tell you it’s “only an ankle’s width,” and your ankle will disagree. Use objective measures—weather, recent temperatures, local reports—not intuition alone.

Guided trips vs. going solo

If you’re new to glacier travel or uncomfortable with the idea of being the person who needs a rescue, hire a guide. Guides provide the technical skills, route knowledge, current conditions, and reassurance that your crampons are not merely fashion statements.

When to choose a guide

- You lack glacier travel or crevasse rescue training.

- You’re unfamiliar with local weather and terrain.

- You want efficient photography time without carrying all safety responsibilities.

- You prefer structured logistics and gear.

Photography tips for the ice cave aesthetic

You can take striking images in the caves, but you’ll need to control light, exposure, and cold. The blue of ice can trick your camera’s white balance; the dynamic range is dramatic; the interior is wet and likely to fog up lenses.

Practical photo advice

- Use a tripod for long exposures; headlamps and LED panels make great color sources.

- Shoot in RAW and adjust white balance later to recover blues and greens.

- Keep spare batteries warm close to your body; cold kills battery life.

- Protect gear in dry bags and wipe condensation as temperatures change.

Environmental stewardship and Leave No Trace

These caves are sensitive and often on fragile glacial terrain. Your footprint can be literal and consequential: compacted snow, trash, graffiti, and accidental collapse caused by heavy group activity are real harms.

How to minimize impact

- Stay off delicate features and avoid carving or sawing at ice.

- Pack out all trash and human waste (consider a WAG bag for overnight trips).

- Use established campsites and trails where possible.

- Leave cave interiors alone unless scientifically supervised or legally permitted.

Local history, myths, and lore

Mount Shasta attracts more than hikers; it attracts storytellers. From spiritual claims to Native American legends, the mountain is part geology and part mythology. The ice caves have their share of tales—some humorous, some earnest, many unverifiable—but they all add to your sense that you’re walking in a place with personality.

A note on lore

If someone tells you a cave cures ailments or is the site of a secret city, enjoy the story but don’t substitute it for helmets, crampons, or common sense. Your sore muscles will listen to evidence; your neighbor’s prophecy will not.

Sample day plan: a pragmatic itinerary

This is a conservative, safe day plan that assumes you’re moderately fit and heading out in late winter or early spring. Tailor to your conditions and check current reports.

- 05:00 — Leave your lodging; arrive at trailhead before dawn to secure parking.

- 06:00 — Begin approach from Bunny Flat or chosen trailhead with headlamp on.

- 08:30 — Reach glacier edge; transition to boots, crampons, harness; brief safety check.

- 09:00 — Move toward cave viewing area with rope on if in glacier terrain.

- 10:00 — Arrive at cave rim; assess stability; photograph or view from safe distance.

- 11:00 — If conditions and safety permit, enter cautiously for short periods only, keeping helmet on and maintaining escape routes.

- 12:30 — Retreat to a sunny spot for lunch, rehydrate, and reassess weather and route.

- 14:00 — Begin return, watching for late-day warming and possible changes in snow conditions.

- 16:00 — Back at trailhead; debrief and report any unusual cave changes to rangers.

Time margins and contingency

Allow extra time for route-finding, bad weather, and slow-moving group members. Always have an exit plan and a turn-around time before you reach the objective.

Emergency actions and rescue considerations

If something goes wrong, speed and clarity help. Below are general steps; for serious incidents call emergency services and use your satellite device if cell service fails.

- If someone is injured and able to move, get them to a sheltered, warm place and begin basic first aid.

- For cardiac arrest, severe trauma, or unconsciousness, call or signal for emergency rescue immediately; begin CPR if trained.

- If someone is dropped into a crevasse and roped, do a self-arrest and initiate crevasse rescue protocols.

- If you have a satellite messenger or PLB, activate it and provide your coordinates and nature of emergency.

- Stay calm, manage hypothermia risk, and ration warm fluids and calories.

Reporting changes to caves

If you witness a significant collapse, new dangerous overhangs, or unusual water surges, report them to the ranger district so others can be warned. Part of stewardship is contributing to collective safety.

Common mistakes new visitors make

You will probably recognize yourself in at least one of these. If not, you’re lying to yourself and possibly to the group.

- Underestimating the sun: bright days can cause rapid melt and instability.

- Ignoring avalanche bulletins: they’re not optional bedtime stories.

- Entering caves without helmets: ice falls and roof collapses are not cinematic but very real.

- Relying on outdated blog posts: conditions change; so should your plan.

- Overconfidently unsupported solo travel on glaciers: it’s a fast track to trouble.

How to prepare mentally

Being comfortable in ice caves requires an acceptance of impermanence. You’re going to stand inside something that might not exist in a few months, or might not exist five minutes after you leave. There’s a strange tenderness to that: it helps you take better photos and pack fewer regrets.

Bring curiosity—and restraint

Curiosity will make you notice colors and textures; restraint will keep you alive to tell the story. Balance both.

Conservation actions you can take after the visit

You can be useful to the mountain even after you’ve gone home.

- Share accurate, non-specific trip reports with the ranger district (avoid exact cave coordinates if they encourage risky visitation).

- Volunteer for trail maintenance or educational programs.

- Donate to local conservation organizations that protect Mount Shasta’s wilderness.

- Encourage responsible behavior among friends: no bragging about risky solo entries.

A small practical packing checklist

This is a compact checklist you can print or copy into your phone. Nothing fancy—just useful.

- Helmet, headlamp, spare batteries

- Crampons, ice axe, harness and rope (if entering glacier terrain)

- Insulating layers, shell, gloves (multiple)

- Food, water, thermos with warm drink

- Map, compass, GPS

- Satellite messenger or PLB

- First aid kit and emergency bivy

- Camera + tripod + spare batteries

Final thoughts and a personal nudge

You’re about to approach a feature of nature that’s equal parts majestic and treacherous. That combination is what makes it unforgettable and what demands respect. You don’t have to be daring to enjoy Mount Shasta’s ice caves; you just have to be informed, prepared, and humble about your chances with ice.

If the mountain seems to be making you feel small, that’s not a bug—it’s a feature. You will also leave with stories that make your friends slightly envious and extremely smug when you show the photos. You will be tempted to tell them you “found” a cave on your own; instead, tell them you followed safe practice and good advice, and then let the photos do the rest.

Remember: these caves are temporary sculptures created by forces that don’t care about your itinerary. Treat them with curiosity, distance, and the same dignity you’d give an old friend who drinks too much at family dinners. If you bring snacks, bring ones you don’t mind sharing—because a small act of kindness on the trail often returns in good stories and in someone else’s extra jacket when you forget yours.

If you want, I can prepare a printable gear checklist, a sample map with reputable sources for topographical maps and current conditions, or a short packing list formatted for mobile viewing. Which would you like next?