?Have you ever stood in front of a sculpture, nodded solemnly, and hoped your face made it sound like you understood what you were looking at?

This image is property of images.unsplash.com.

Siskiyou Arts Museum and the Small Triumph of Pretending I Know About Modern Sculpture

You arrive at the Siskiyou Arts Museum with the good intentions of being cultured, but you also have the terrible honesty of knowing you Googled half the artists in the car on the way there. The museum in Mount Shasta, CA, will reward you for both impulses: it has displays that ask for concentration and others that reward a wandering eye. You leave feeling slightly more intelligent than when you came in, which is the exact feeling you were aiming for.

Why this museum feels like a small miracle

The Siskiyou Arts Museum is modest in size but uncommonly generous in personality. It is the sort of place where the coffee is meaningful, the clerk knows which local sculptor has a thing for repurposed metal, and the maps are the sort you actually look at because you want to know what the curator eats for breakfast. You will notice details: local stories stitched into labels, a willingness to mix serious art with moments of mischief, and a landscape outside that keeps insisting the world is larger than the gallery.

About the Siskiyou Arts Museum

The museum sits in the foothills of Mount Shasta, a town whose very name makes you expect clouds and prophecy. The Siskiyou Arts Museum was founded to showcase regional artists while inviting national and international work through rotating shows. Its modest footprint makes it intimate; you rarely feel swallowed by echoing marble halls here, and that gentleness is the museum's charm.

Mission and community role

The museum's mission emphasizes community engagement, arts education, and the celebration of both emerging and established artists. You will find programs for children, talks for adults, and opportunities for local creatives to show work. It behaves less like an aloof temple and more like a civic room where people can convene and learn — the sort of place you would go if you wanted to bring a nervous friend and make them feel cultured without intimidation.

History and development

The museum emerged from grassroots efforts by local art advocates and donors. Over years it has grown from a gallery with a few local shows into an institution that attracts touring exhibits and regional attention. Its development reflects the broader story of Mount Shasta’s cultural ambitions: a small town with outsized creative energy. You will appreciate how the museum manages to be both serious in curatorial practice and playful in programming.

This image is property of images.unsplash.com.

Mount Shasta, CA: the setting and its influence

Mount Shasta is part geology, part myth, and part independent coffee shops that insist on using beans two towns over. The mountain itself looms like an audience member who never leaves. The local culture — a combination of outdoor enthusiasts, artists, and long-term locals — colors the museum’s personality. When you exit the gallery, it’s common to see hikers with hiking shoes and a brochure in one hand, a canvas with an unfinished watercolor in the other.

Natural context and artistic inspiration

The natural environment around Mount Shasta is a primary visual and atmospheric influence on the museum’s exhibitions. Landscapes, seasonal light shifts, and a climate that encourages outdoor art tend to show up in the collection and programming. You will notice an appetite for materials taken from the land — stone, wood, metal — and a tendency toward contemplative works that echo the mountain’s presence.

Other cultural assets in the area

You can pair a museum visit with local galleries, seasonal festivals, and music series. Small theaters and community arts centers host performances and workshops that feed into the museum’s programming. If you are seeking a weekend of art and nature, Mount Shasta arranges itself into an affordable and accessible package.

Practical visiting information

Your visit will be smoother with a little planning. The museum’s size means you can see its main exhibits in anywhere from 45 minutes to two hours, depending on how seriously you take label copy. There is parking, and the downtown area is pedestrian-friendly if you want to combine your trip with local food.

Hours, admission, and contact basics

You will want to confirm hours before you go because smaller museums sometimes vary seasonally. Admission is generally modest, with discounts for seniors, students, and families. There are member benefits if you think you might become a repeat visitor, and the staff is always generous with recommendations for local eateries and nearby trails.

Accessibility and family friendliness

The museum emphasizes accessibility. The layout is compact with ramps and accessible restrooms, and staff can provide tactile or audio resources for visitors who require them. Family programming encourages kids to make art or participate in scavenger hunts — helpful if you’re traveling with children and want them to feel engaged rather than tolerated.

This image is property of images.unsplash.com.

The building and galleries

The architecture of the museum is warm and unpretentious. High ceilings give space to tall works, while smaller rooms allow intimacy for delicate pieces. Lighting is curated thoughtfully to flatter materials without creating glare. You will notice how careful placement amplifies the mood of each exhibit.

Permanent collection areas

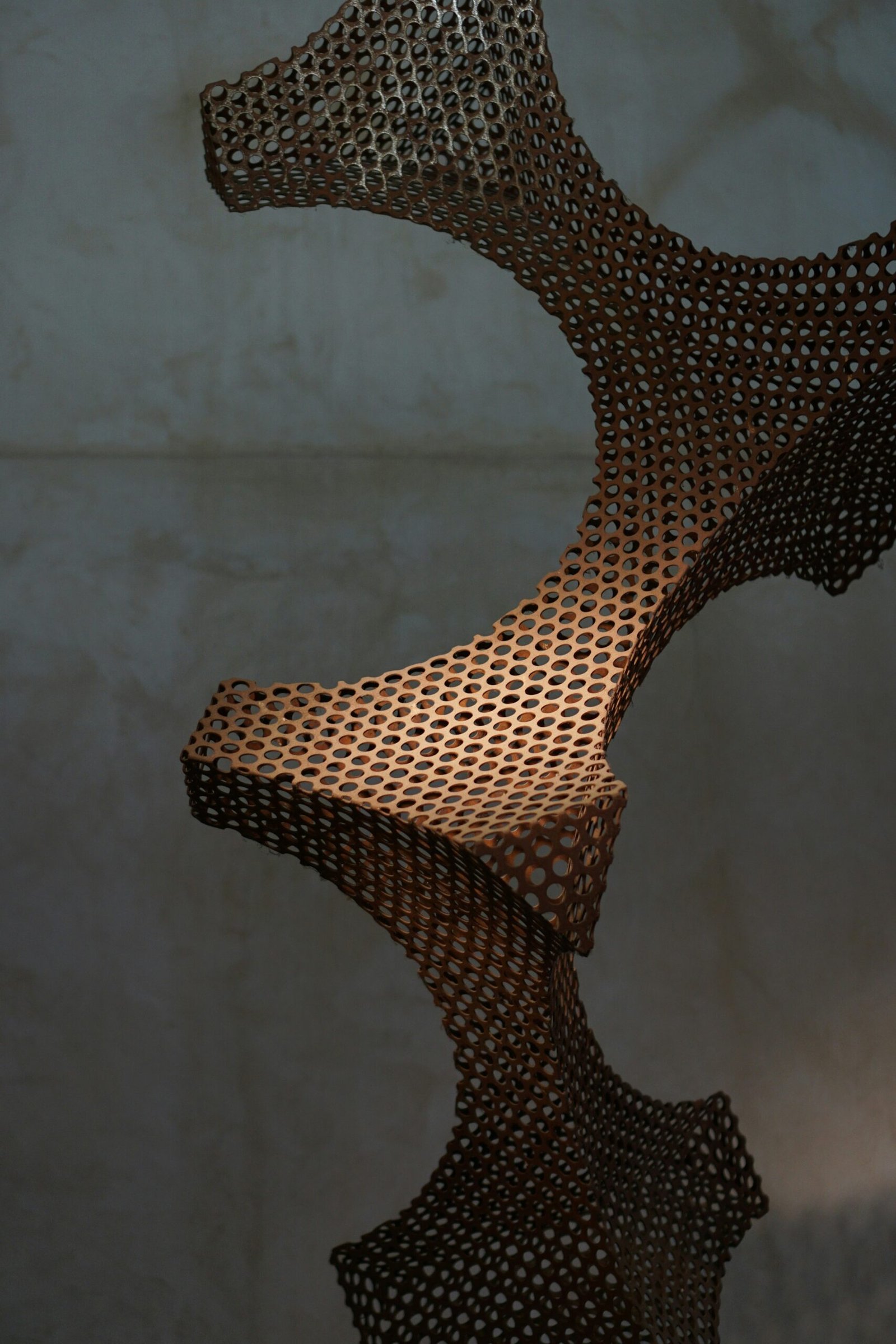

The permanent collection is a thoughtful mixture of regional artists and mid-career names. Even if it’s not a list of household names, the works often tell a coherent story about place, material, and the relationship between human craft and the landscape. You may find a large, rusted steel assembly across from a delicate ceramic series — contrast that makes both pieces more interesting.

Rotating and temporary exhibitions

Rotating exhibitions are where the museum stretches. The shows can be contrarian, quietly provocative, or simply unexpected, bringing work from further afield and encouraging viewers to change their assumptions. They often include contemporary sculpture, which is a good place for your admitting confusion to feel like a shared experience rather than a failing.

Understanding modern sculpture (without ruining your confidence)

Modern sculpture can feel like an arranged conspiracy of objects that refuse to be comfortable. But you don’t need a PhD to enjoy it. Sculpture’s core is form, material, and the space it occupies. Modern sculptors often interrogate the idea of what a sculpture can be — whether by manipulating scale, material, or context. You will find that paying attention to your own bodily response — how the work makes you want to walk around it, touch it, or cross your arms — is as valuable as any curatorial essay.

Materials and techniques: what to look for

Modern sculptors use almost anything: bronze, steel, wood, found objects, plastics, and mixed media. This variety is both liberating and an invitation to misinterpret. Rather than trying to decode intentions, notice how the material behaves: does metal look raw, shiny, or intentionally flawed? Is wood smoothed into silence or left splintered and loud? The materials speak about durability, memory, and process.

Table: Common materials and what they often suggest

| Material | Visual/Physical Cues | What it might suggest |

|---|---|---|

| Steel/metal | Cold, reflective, industrial | Strength, modernity, mass-production critique |

| Wood | Grain visible, warm, organic | Memory, craft, natural cycles |

| Stone | Heavy, textured, ancient feel | Permanence, geology, ritual |

| Ceramic | Fragile, glazed, delicate | Domesticity, craft tradition, fragility |

| Found objects | Recognizable items recontextualized | Consumer critique, humor, history |

| Plastic/synthetic | Bright colors, sheen, malleable forms | Modern life, disposability, irony |

Scale, space, and the viewer

You will often see work that demands movement: large pieces you walk around, installations you enter, or suspended objects that alter your perception of ceiling height. Sculpture invites you to consider your own body. If a piece makes you want to step back, step closer, or change angle, it’s already doing its job. Treat the impulse to move as a legitimate part of interpretation.

How to pretend you know about modern sculpture (and maybe actually learn a bit)

You will sometimes want to sound like you understand what you're looking at without sounding like a peacock. A blend of curiosity, a few reliable phrases, and sensible body language will carry you farther than you expect. The point is not to fake insight but to perform engaged attention — and if you pick up a real observation, that’s even better.

Phrases that make you sound observant (table)

Use these lines when you need to fill a silence. They are honest-sounding and avoid vague pretension.

| Situation | Phrase to say | Why it works |

|---|---|---|

| Not sure about the materials | “I like how the material resists looking finished.” | Sounds specific; shows attention to process |

| Want to comment on scale | “The scale makes you aware of your presence in the room.” | Body-centered observation; safe |

| Not understanding intent | “It makes me think about where ordinary objects belong.” | Connects work to daily life without claiming authority |

| If someone asks for your opinion | “I keep circling it because I keep discovering something new.” | Suggests curiosity and nuance |

| When an abstract form confounds you | “There’s a kind of narrative suggested, but it won’t be pinned down.” | Acknowledges complexity without fake certainty |

Body language and toured competence

You will want to adopt a few humble gestures: steady, interested eye contact with the piece, slow intentional walking around the work, occasionally leaning slightly in to read labels. If someone asks if you know the artist, nod and say something like, “I’m getting to know them,” which implies study without claiming dominance. Hold your catalog like a scholar and consult it intermittently.

Interpreting labels and wall text

Labels are your friends, though some are written in the dense language that can intimidate. Read the artist statement and production notes; they often contain clues about material choice and process. If the text uses jargon, extract the verbs—what the artist did, not the theoretical adjectives. You will find more insight in process descriptions than in grand claims.

How to extract meaning without believing every curator

Curatorial voice can be enthusiastic, but you don’t need to agree with every interpretation. Ask yourself what the work does physically and emotionally. Does it produce a memory, a discomfort, amusement, or nothing at all? Your immediate response is valid. If label copy seems hyperbolic, smile and treat it as one voice among many. Museums host arguments; you can choose which you agree with.

Workshops, tours, and programs: when to ask questions

If you want to move beyond polite commentary, go to a gallery talk or a docent-led tour. These programs are designed for people who will admit they don’t know and want to learn. You can take notes, ask simple questions, and watch others ask complicated ones you can borrow later. The staff is usually delighted when someone is genuinely curious; you will be doing them a favor.

Educational opportunities for hands-on experience

The Siskiyou Arts Museum offers occasional workshops and classes where you can work with materials artists use. Getting your hands dirty with clay, metal, or wood reduces the mystique substantially. You will return to the galleries with practical empathy for the labor behind finished pieces, and your commentary will sound both honest and informed.

Notable artists and works you might encounter

The museum rotates shows, so you can’t predict exactly who will be on view. However, typical offerings include regional sculptors working with found objects, more formal mid-century pieces, and international contemporary installations. Even if you encounter an artist you don’t recognize, you can use context: look at the year, materials, and any regional ties noted in the label.

Patterns to notice in regional art

You will see themes of land, craft, and survival. Materials harvested or repurposed from local industry show the dialogue between place and work. Regional artists often repurpose tools, mining remnants, and natural detritus, giving these items a new symbolic life. Looking for those patterns makes you a better reader of the collection.

Photography, social media, and museum etiquette

The museum usually allows photography for personal use but check policies in each gallery. If flash is prohibited, respect that — sculpture can be sensitive to light, and compulsion to Instagram should not damage a work. Be mindful of crowding; sculptural works often require space to appreciate.

Posting responsibly

When you photograph a piece, include credit to the artist and the museum in your post. Avoid speculative claims about meaning; instead, share what the work made you feel or notice. People appreciate honesty more than pretension.

Food, coffee, and the best way to end the visit

The museum occasionally hosts small events with local food vendors. If you want to end your visit pleasantly, take a walk in the surrounding neighborhood or sit in the museum’s gathering space with coffee. This is when you will process what you have seen and make up a confident-sounding interpretation you can test in conversation.

Nearby places to eat and decompress

Mount Shasta has a few solid cafés, diners, and bistros where you can articulate your newfound art knowledge to a sympathetic stranger. The region favors hearty portions and locally-sourced elements. If you became pretentiously moved by a piece of woodwork, a locally brewed beverage will help separate your emotions from your hunger.

Why pretending can be a useful practice

You will sometimes find that pretending to know buys you time to look, ask, and actually learn. The performance of competence is a social lubricant that can lead to real understanding. If you bluff your way into a conversation with a docent, you may leave with free knowledge you did not have before. Pretending is not about deceit; it’s about creating an opening for curiosity.

The humility of admitting ignorance

Ironically, the most believable performance of knowledge includes the admission of not knowing. Saying, “I’m not sure what this is about yet,” is both honest and sophisticated. It signals openness and invites others to share their interpretations. Museums are forums for exchange, and your admission can facilitate conversation.

Curatorial decisions that shape what you see

Understanding why things are placed where they are can enhance your viewing. Curators control lighting, proximity, and sequencing — all of which create narratives through placement. If two sculptures are boxed together, they were likely chosen to respond to one another. You will appreciate the invisible hand that arranges these conversations when you start to notice recurring pairings or color echoes.

The role of the visitor in finishing the work

Many contemporary works depend on your participation — not in the literal sense of touching, but in the mental activity that completes the piece. Your movement, memory, and associations are all part of the sculpture’s life. Treat this as an invitation to be active rather than passive.

Safety, conservation, and why you can’t touch everything

Conservation is the unseen bureaucracy of museums. Oils from hands, shifts in humidity, and stray coffee cups can damage materials. Respect barriers and signage. You will feel chastened the first time a guard gives you an earnest look, but you will also appreciate knowing the care that preserves work for future visitors.

Behind-the-scenes: conservation basics

The museum likely has a conservation plan to regulate light exposure and humidity, especially for delicate materials like textiles or paper. Sculptural materials require their own specialized care — metals may be treated to prevent corrosion, wood must be maintained to avoid drying or pest infestation. Knowing this gives you a new respect for the stillness museums impose.

If you want to go deeper: books, podcasts, and further learning

You can build a modest library of approachable criticism and history. Look for artists' monographs, accessible museum catalogs, and podcasts that interview sculptors. Practical studio books that describe processes and materials also demystify the labor behind finished pieces. You will find that reading about process makes exhibitions more intelligible.

Recommended types of resources

Seek out:

- Exhibition catalogs from recent shows (they often include essays that are readable).

- Interviews with artists that describe practice and intention in plain language.

- Studio books and craft manuals that explain technique.

These resources will help your future visits feel less like performances and more like informed curiosity.

The small social rituals of museumgoing

You will encounter subtle social codes in museums: quiet voices, considered pacing, and a willingness to exchange a few sentences about an unfamiliar piece. These rituals make the space safe for contemplation. Acting with attentiveness — putting your phone away for a bit, allowing someone else to stand in front of a work — creates a small communal civility.

How to make museumgoing more enjoyable for everyone

Be courteous in traffic lanes near popular pieces, step aside to let others view, and keep conversations at a low volume. If you want to gesticulate, do so gently — sculptures respond badly to elbowing. Museums are not stadiums; the shared quiet is the real luxury.

Final thoughts: your small triumph and the honest conclusion

You will likely leave the Siskiyou Arts Museum feeling both slightly accomplished and pleasantly chastened. The small triumph of pretending you know something about modern sculpture becomes a larger triumph when you pair that pretense with curiosity. The museum offers an environment where pretense can quickly turn into understanding: you ask a question, you listen, you look again, and sometimes you catch yourself actually thinking in new ways.

On returning and building a habit

If your first visit felt like a performance, plan a second visit as a study. Attend a talk, take a workshop, or volunteer for a docent program. Your initial bluff will be replaced by a gradual competence that tastes better than any pretended authority. Over time, you will notice patterns, favorite materials, and artists whose work consistently rewards attention.

Useful quick-reference tables

Table: Quick facts at a glance

| Item | Detail |

|---|---|

| Location | Mount Shasta, CA |

| Typical visit length | 45 minutes — 2 hours |

| Admission | Modest; discounts available |

| Accessibility | Ramps, accessible restrooms, programming for varying needs |

| Photo policy | Often allowed for personal use; check specific exhibits |

| Parking | On-site and street parking available |

Table: Do and Don't at the museum

| Do | Don’t |

|---|---|

| Read labels and ask staff questions | Touch artworks without permission |

| Walk slowly and circle sculptures | Block doorways or crowd around a single view |

| Attend a talk or workshop to learn more | Assume that silence means you must know everything |

| Respect signage and barriers | Use flash photography against instructions |

You will find that a museum visit becomes less about performing and more about participating if you treat it as practice in attention. Each time you pay attention, you increase your ability to appreciate nuance without needing to perform insight.

A parting anecdote and an invitation to curiosity

On one visit to the museum, you may overhear someone saying, “It looks like my grandmother’s attic,” and another person reply, “Yes, and it smells like an argument between geology and thrift.” That exchange — equal parts bemusement and sincerity — captures the Siskiyou Arts Museum’s atmosphere. You will recognize that most people are not there to be judged; they are there to be moved, confounded, amused, and occasionally enlightened.

You may leave thinking you still don’t truly know modern sculpture, but that’s fine. You will have practiced the small triumph of pretending, and in the practice you will have learned real things. The mountain will still be waiting, the town will still have its coffee, and the museum will keep arranging objects into conversations that insist you show up, take another look, and maybe, just maybe, say something worth remembering.